The Great AI Fallacy

Yann’s Facebook AI lab launch triggered me to think about what what artificial intelligence means. It also triggered me to engage more with public dialogue around AI. I wrote one of my first articles about the launch for The Conversation.

Rather than imposing on people one of the myriad academic definitons of AI (strong or weak or whatever), it seemed more sensible to get a sense of what the public think it means.

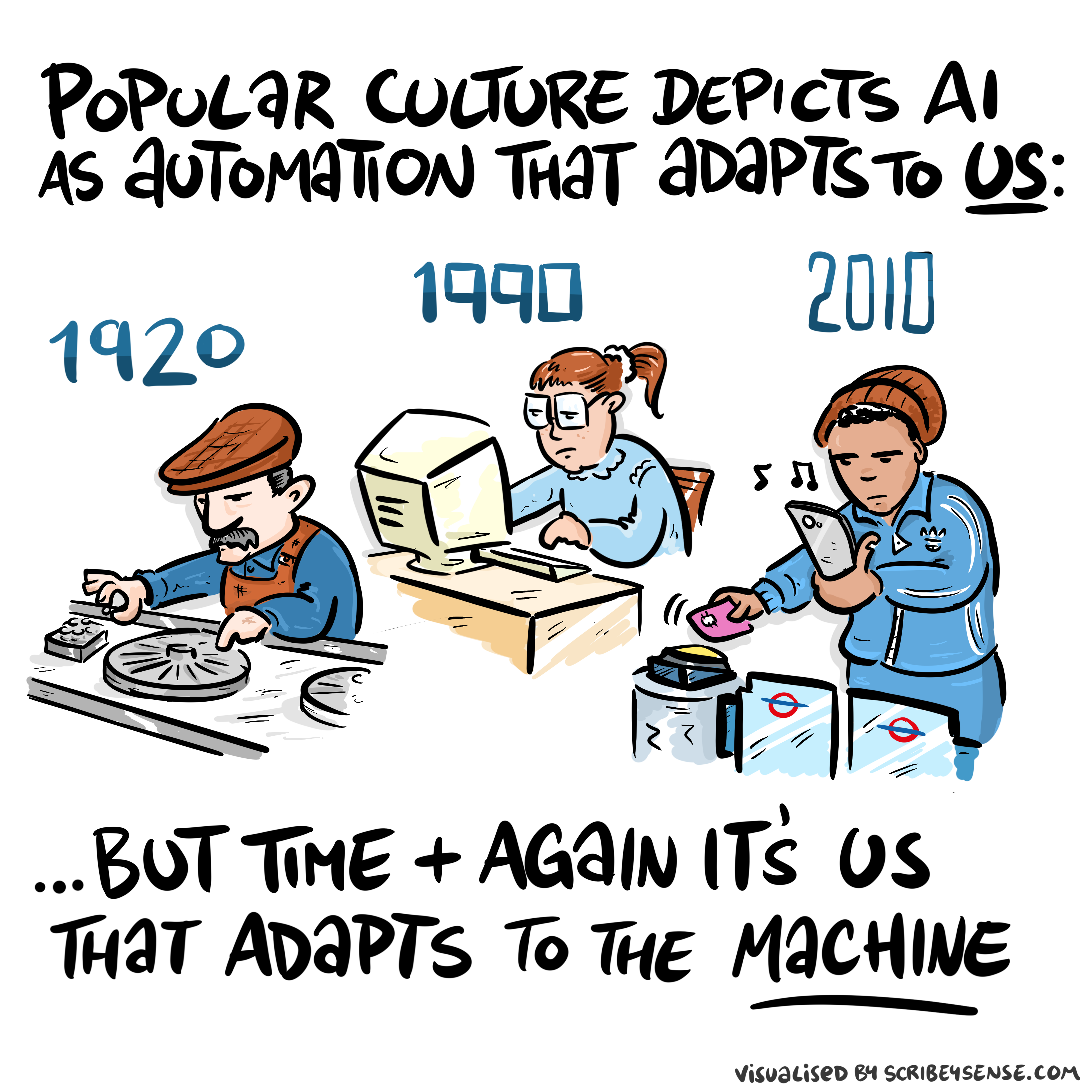

People have different opinions, but my best way of summarising the general opinion would be to say that when they are presented with AI, people assume they are being given a form of technology that is capable of adapting to them. This stands in stark contrast to previous waves of technology and automation, each of which forced the human to do the adapting.

In 2020 at the Information Engineering Distinguished Lecture I gave a talk1 titled Intellectual Debt and the Death of the Programmer. I touched on the idea that people think that we’re building AIs that can accommodate them and I called this phenomenon “the great AI fallacy”. At the time we saw no sign that the machine was accommodating the human, in fact we saw precisely the opposite. Dan captured this very nicely for his drawing for Chapter 9.

Dan Andrews' illustration for Chapter 9, A Design for a Brain. See scribeysense.com

Dan Andrews' illustration for Chapter 9, A Design for a Brain. See scribeysense.com

I revisited the phenomenon in Chapter 9 of the book.

I call this phenomenon ‘the great AI fallacy’. The fallacy is that we think we have created a form of algorithmic intelligence that understands us in the way we understand each other. A technology that gives us the same feel for it as we have for our fellow human.

The Atomic Human pg 257

But I also revisited my assessment of whether the fallacy will be maintained. With the advent of generative AI and large language models I do think we are seeing the first signs of machines that are able to adapt to us.

With generative AI and large-language models such as ChatGPT we can now build machine-learning systems that provide plausible communication between human and machine using the languages humans have developed for themselves, rather than for their machines. This new frontier presents a promising route to ending the AI fallacy and bringing the technology we’re producing into line with people’s expectations.

The Atomic Human pg 258

This has a myriad of implications for the challenges I was presenting in 2020. We’ve outlined some of our new research directions to address them in some of our papers … so watch this space … maybe a future Dan Andrews will draw a new panel for 2040 where the humans have turned the tables …

-

Christian Cabrera, Andrei Paleyes, and Neil D. Lawrence. 2024. Self-sustaining Software Systems (S4): Towards Improved Interpretability and Adaptation. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on New Trends in Software Architecture (SATrends ‘24). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 5–9. https://doi.org/10.1145/3643657.3643910

-

Diana Robinson, Christian Cabrera, Andrew D. Gordon, Neil D. Lawrence, and Lars Mennen. 2024. Requirements are All You Need: The Final Frontier for End-User Software Engineering. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. Just Accepted (December 2024). https://doi.org/10.1145/3708524

-

Christian Cabrera, Viviana Bastidas, Jennifer Schooling, and Neil D. Lawrence. 2024. The Systems Engineering Approach in Times of Large Language Models. 58th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS-58). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.09050

-

The talk outlined my research programme for the next five years. Main funding has been provided a UKRI Senior AI Fellowship. We refer to the project as AutoAI and you can find the strategic research agenda for it here. ↩

Click to see what the machine says about the reflection and the book

Machine Discussion

NL: How are the challenges identified in this talk from 2020 addressed in these three papers?

Can you call out in particular how our perspective on “The Great AI Fallacy” might change if the ideas in these papers were realised.

Can you also identify the technological trends that might have shifted the landscape since 2020.

Claude: Let me analyze how the challenges and concerns raised in Neil Lawrence’s 2020 talk about “The Great AI Fallacy” relate to and potentially evolve through the ideas presented in these three more recent papers.

The Great AI Fallacy identified in the 2020 talk was the implicit promise that AI would be the first wave of automation where machines adapt to humans, rather than humans adapting to machines. The talk warned that without significant changes to how we design and deploy these systems, we risked being “enslaved by super-ignorance” rather than super-intelligence.

Key shifts and developments evident in the 2023-2024 papers:

Technological Shifts Since 2020:

The “Great AI Fallacy” Assessment: While these papers provide more sophisticated frameworks for human-AI collaboration, they don’t fully invalidate Lawrence’s core concern. Instead, they suggest a middle path:

However, many of the fundamental challenges Lawrence identified around intellectual debt and system complexity remain relevant. The papers propose frameworks to address them but successful implementation still requires significant changes to how we approach software development and deployment.