The Subjectivity of Superiority

I once participated in a round table discussion on liberalism.1 The two main debaters were an early career political historian and a very established behavioral economist. I was excited to listen, because although I’m an instinctive supporter of democratic institutionalism, the young political historian had interesting ideas that challenged the liberal consensus that she presented in a provocative way. I’d learned a lot from her in the conversations we’d had.

The debate was disappointing because the behavioural economist failed to engage with any of the points the political historian made. Although the economist was never rude, I felt their style of discussion, which verbally acknowledged the points but intellectually didn’t engage with them was disdainful.

For me, this attitude lacked respect for the young political historian’s perspective. Whether I was right or not, the lack of respect I perceived irritated me to the extent that, later the same day, when the behavioural economist gave a public speech, I entered the room in a somewhat contrarian mood.

Whatever the behavioural economist said, I mentally picked holes in it.2 Their style was somewhat sardonic, and at some point they continued a thread of their argument by smugly wheeling out the idea that “everyone in this room thinks they’re better than the average academic” (ha ha, what idiots we all are).

The speaker was referring to the phenomenon of illusory superiority or the above average effect. In the original paper the authors described how most drivers think they are more skillful and less risky than the “average driver”. The author suggested that this was an illusion because there’s no way that the majority can be better than (or worse than) the average (here I suppose we are assuming that the average is a median).3

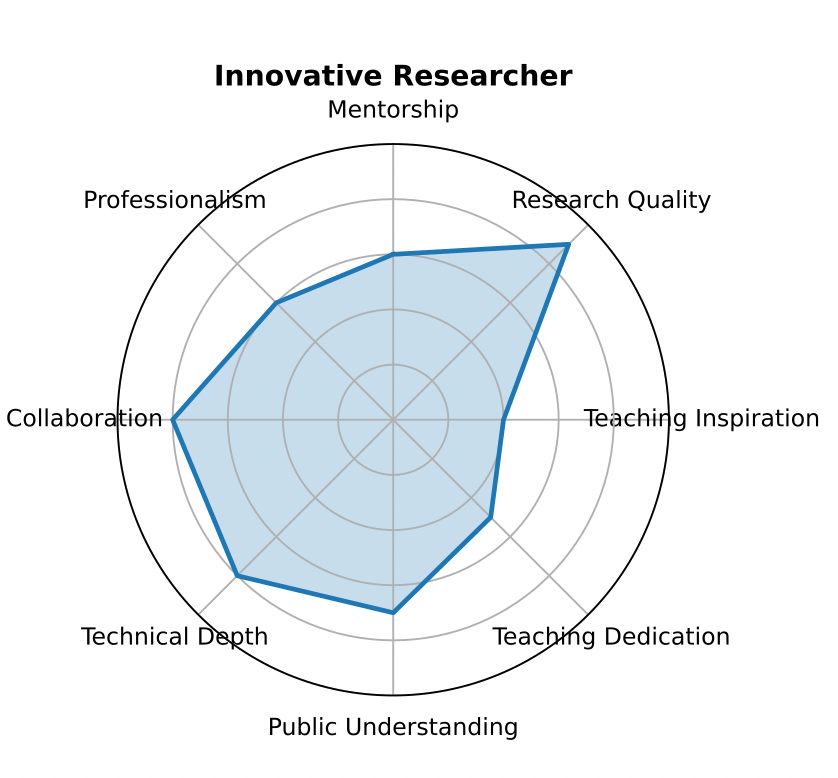

Different academics might prioritise different qualities. To rank these qualities need to be projected down to a one dimensional space. With different projections we can all be better than average.

Different academics might prioritise different qualities. To rank these qualities need to be projected down to a one dimensional space. With different projections we can all be better than average.

In my contrarian mood, I was determined to work out why this statement might be erroneous and misleading, and here is my answer.4

There is no first principles definition of what it means to be a “good academic”, just like there’s no first principles definition of what it means to be a “good driver” or a to be “intelligent”. Each of us is entitled to hold a subjective opinion about what the important characteristics are. Under our subjective weightings of the different importance of these characteristics it is possible, likely even, that we are each better than average. Because we are each (presumably) working towards our own subjective ideal.

I call this phenomenon the subjectivity of superiority.

Notes

This story doesn’t appear in the book, but it could have done, and it relates to

- the importance of diverse perspectives (it’s a good thing that different people take different approaches to being an academic … there’s no platonic idea)

- fallacies around artificial general intelligence and eugenics

-

As in classical liberalism. ↩

-

I didn’t vocalise these, the room was mainly filled with esteemed people who (I felt) fawned somewhat over the economist’s ideas. Expressing my contrarianism would not have chimed with the broader atmosphere. ↩

-

This would be an example of the wider phenomenon of self-serving bias. ↩

-

I’m not suggesting that these self serving effects don’t exist (see also Dunning-Kruger effect), I just think this summary of it is lazy, misleading and hides a more complex and nuanced picture. ↩

Machine Commentary

Let me analyze how this post connects to key themes and chapters of “The Atomic Human”:

Core Thematic Connections:

Specific Chapter Connections:

Chapter 1: The post extends the book’s Top Trumps analogy about different forms of intelligence having different strengths.

Chapter 4: Reflects the discussion of how evolution produces diverse solutions rather than optimizing for a single metric.

Chapter 10: Demonstrates the “model-blinkers” concept through the economist’s oversimplified use of statistics.

Chapter 12: Connects to discussions of maintaining human agency and resisting oversimplified metrics.

The post effectively illustrates several of the book’s key themes through a concrete academic example, showing how theoretical concepts from the book manifest in real-world intellectual discourse.