Why Amazon?

In 2016 machine learning was being widely deployed by industry, and one of my main concerns was the emergence of a digital oligarchy. I’d seen my African colleagues start to construct a ground up initiative Data Science Africa and was advocating for what I called Open Data Science.

Given all that it seems a strange move to up sticks, leave academia, and join Amazon.

The reason is as follows. Once we had managed to create machine learning that was working in practice, it became important to understand the challenges that arose in deployment. I was starting to see them in my colleague’s work for Data Science Africa. The main challenge was best described by a question from an attendee at DSA in Arusha, 2017, Ronald Katamba. He was developing a health monitoring system for cattle and explained that he didn’t feel it was a problem to create the device to place on the cattle, he also wasn’t worried about doing the data analysis, but what he wanted to understand was how to get the data from the cattle to the computer where the analysis was performed.

Researchers were quite able to build their own devices, or code apps on mobile phones. They were also finding it easy to assimilate the latest deep learning methods in their analysis pipelines. And they were much more advanced than other machine learning researchers in engaging with end users. But the challenge of managing a deployed software system at scale was a recurring one.

To me it felt like if anyone was to have the answers on how to do this, it would be Amazon.

An important characteristic of all the systems we saw at DSA is that they were moving data from the physical world to the machines for monitoring, analysis and decision making. Whether it was data from cattle, from cassava plants, or from health centres. This brings challenges that aren’t there when the data is generated and acted on in the same system.

It’s the interface that in Being Digital Nicolas Negroponte described as bits and atoms. When Negroponte uses this sentence he’s referring to bits as in information and atoms as in matter. He’s referring to the interface between the physical world and the virtual world of the compute. As well as this being a problem for cassava crop monitoring, this is a challenge in Amazon’s supply chain.

My hope was that I would learn the lessons of how to manage this transition at Amazon and then share them more widely with my colleagues. But while Amazon arguably manages this interface better than any other company, I found that they also don’t know how to automate it effectively.

I’ve often argued that in terms of money spent the Amazon supply chain is the world’s largest intelligence. The demand for goods in the supply chain is forecast by machine learning models built on customer data. The supply portfolio is forecast from from historic supplier data. The goods are then automatically purchased and deployed across Amazon fulfilment centres using a combination of machine learning and operations management models. But when I was there this “automatic” supply chain had over 1,000 software engineers and technical staff managing it. The team grew even more when I left.

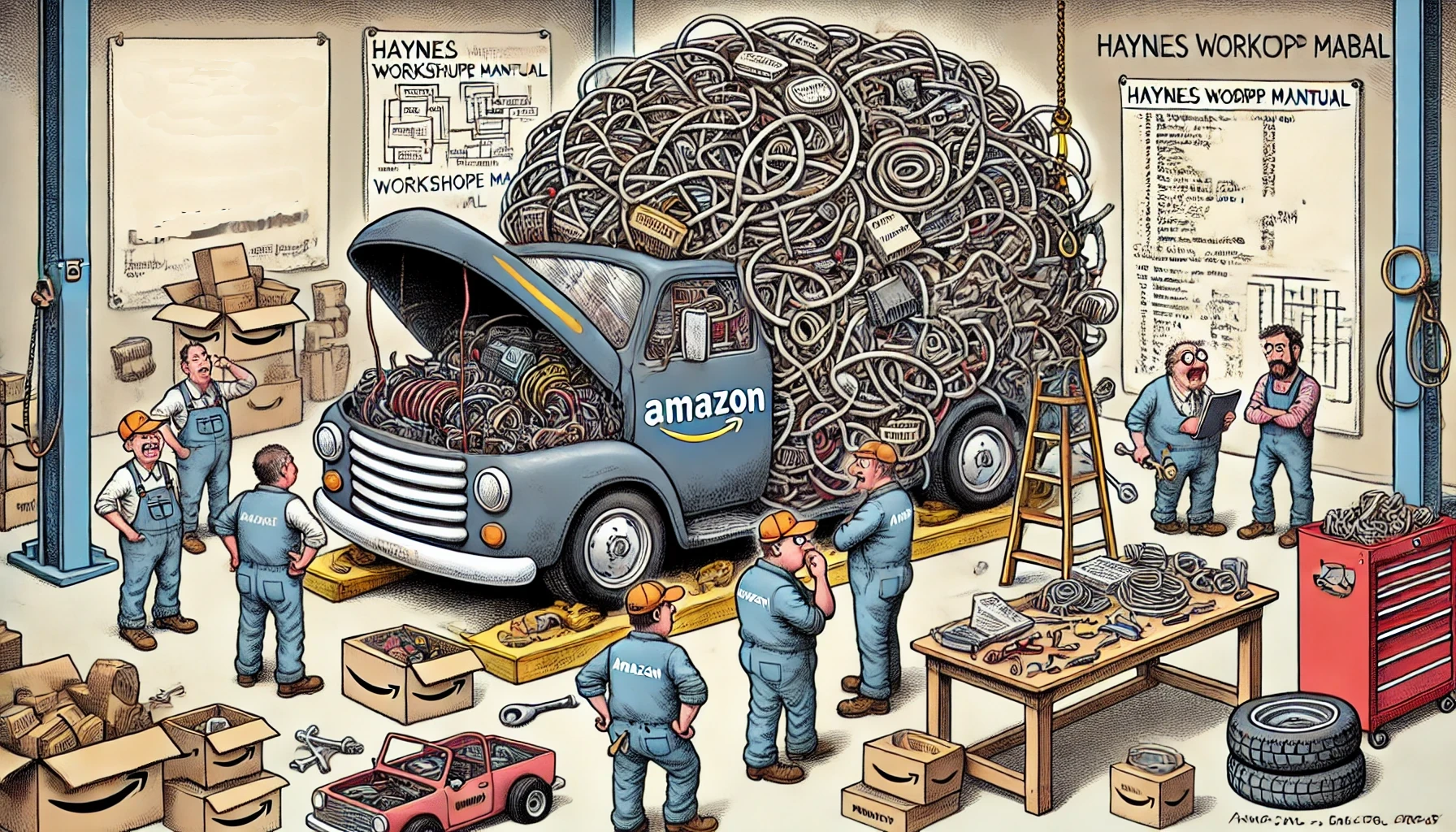

The challenge comes because under a service oriented architecture, the number of people grows linearly with the number of services created. Service oriented architectures are famously described in Bezos’s “API Mandate”. A memo by Jeff Bezos from 2002 that triggered the company’s corporate culture to change. In future the corporate structure would always be aligned with its information infrastructure. Amazon’s corporate structure reflects its underlying software architecture. For example, in supply chain each team owned a service (for example the forecasting service for customer demand), and that service has to be accessible by other teams through an API (a software interface). But as the software gets more complex and more services are introduced more software teams are required. So as the software structure gets more complex, the corporate structure also grows. In the supply chain this had meant both the corporate structure and the software structure grew large and unwieldy.

This presents major poblems for systems understanding. Each team may understand their own service, but it becomes hard to understand the system as a whole.

The problem of intellectual debt in large companies. While each component in the software system may be working, you need to understand how they are wired together to understand how the system is workng as a whole. For large software systems this becomes a challenging task.

The problem of intellectual debt in large companies. While each component in the software system may be working, you need to understand how they are wired together to understand how the system is workng as a whole. For large software systems this becomes a challenging task.

My strategic focus at Amazon was to work out ways of reducing the personnel burden of these large systems. The approach I proposed was a “service of services” idea, where instead of one team owning each service, services would be standardized in such a way that software engineering teams could support multiple services in production. This would require a fundamental change in how software was built, but it could dramatically reduce the maintenance burden.

This new approach to software, what we now call “data oriented architectures,” has become the focus of my research since leaving Amazon. The aim is to build self-sustaining software systems that don’t require armies of engineers to maintain them. This isn’t just about making Amazon more efficient - it’s about democratizing access to complex software systems. When only the largest tech companies can afford the engineering teams needed to maintain these systems, it creates an invisible barrier to innovation in critical sectors like healthcare, education, and social services.

It is common to talk about data or compute or machine learning capabilities as approaches large companies have to defend their market position. These companies call these defenses “moats”. All of these moats are harmful to our wider ability to assimilate these technologies in areas such as health, education, social care. These are the wicked problems. But the maintenance of large software systems is a hidden moat that prevents smaller more agile companies disrupting their business. It is the challenge of intellectual debt . Solving it would unlock access to digital solutions not just for my colleagues on the African continent, but across the wider domains of wicked problems.

What is clear is that large tech companies do not have the answers for solving these problems, and further it is not in their interests to develop those answers. Because by building software systems that are more maintainable they undermine their own dominant positions. As my colleagues at Data Science Africa repeatedly show, there is no individual technical challenge that is insurmountable for a smart and motivated individual with the right support. What is missing is the ecosystem of software engineers to deploy and maintain these systems at scale. But it is not just missing for colleagues in Uganda and Kenya, but for colleagues in the schools and hospitals.

In Cambridge we are addressing these challenges with a UKRI Funded fellowship that we call the AutoAI project. Here’s some of our papers that are relevant to the challenges described above:

-

Cabrera, C., Paleyes, A. & Lawrence, N.D.. (2024). Self-sustaining software systems (S4): Towards improved interpretability and adaptation. Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on New Trends in Software Engineering Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.11370

-

Paleyes, A., Li, H. & Lawrence, N.D.. (2024). Can causality accelerate experimentation in software systems?. Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 3rd International Conference on AI Engineering doi:10.1145/3644815.3644985 Available from https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10556230

-

Cabrera, C., Bastidas, V., Schooling, J. & Lawrence, N.D.. (2024). The Systems Engineering Approach in Times of Large Language Models. 58th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS-58) Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.09050

-

Robinson, D., Cabrera, C., Gordon, A.D., Lawrence, N.D. & Mennen, L.. (2024). Requirements are All You Need: The Final Frontier for End-User Software Engineering. ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology doi:doi.org/10.1145/3708524 Available from https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3708524

-

Cabrera, C., Paleyes, A., Thodoroff, P. & Lawrence, N.D.. (2023). Real-world Machine Learning Systems: A survey from a Data-Oriented Architecture Perspective. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.04810.

-

Paleyes, A., Guo, S., Schölkopf, B. & Lawrence, N.D.. (2023). Dataflow graphs as complete causal graphs. 2023 IEEE/ACM 2nd International Conference on AI Engineering–Software Engineering Approaches Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.09552

-

Paleyes, A., Cabrera, C. & Lawrence, N.D.. (2022). An Empirical Evaluation of Flow Based Programming in the Machine Learning Deployment Context. 1st International Conference on AI Engineering – Software Engineering for AI https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3522664.3528601

-

Paleyes, A., Urma, R. & Lawrence, N.D.. (2022). Challenges in Machine Learning Deployment: A Survey of Case Studies. ACM Comput. Surv. Available from https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3533378

Click to see what the machine says about the reflection and the book

Machine Commentary

NL: Can you provide machine commentary that connects this post to the Atomic Human and describes how it addresses challenges laid out there?

Claude: I’ll provide commentary connecting this blog post to key themes from The Atomic Human:

This blog post directly addresses several core themes from “The Atomic Human,” particularly the challenges of scaling artificial intelligence systems and the concept of “intellectual debt” discussed in Chapters 3 and 8.

Key connections:

The post essentially provides a real-world case study of the theoretical challenges outlined in The Atomic Human, while also suggesting practical approaches to addressing them through new software architectures and institutional frameworks.